本文转自《Carbon Brief》发表的题为“The Carbon Brief Profile: Japan”的文章。

原文链接:https://www.carbonbrief.org/carbon-brief-profile-japan

日期:2018.06.25

In the third article of a new series on how key emitters are responding to climate change, Carbon Brief looks at Japan’s gradually falling emissions and the ongoing legacy of the Fukushima nuclear disaster.

在有关主要排放国如何应对气候变化的新系列的第三篇文章中,“碳简论”(Carbon Brief)探讨了日本日益减少的排放,以及福岛核灾难遗留的问题。

Japan is the world’s third largest economy and seventh largest emitter of greenhouse gases (GHGs). Its plans for decarbonisation were significantly set back after the 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster led it to move away from nuclear power and expand the use of fossil fuels.

日本是世界第三大经济体和第七大温室气体排放国。 2011年福岛核灾难导致其脱离核电并扩大化石燃料的使用后,其脱碳计划受到严重影响。

Japan’s government now plans to increase both renewable and nuclear power. However, it also intends to build significant numbers of new coal power plants. Japan has pledged a 26% reduction in GHG emissions below 2013 levels by 2030.

日本政府现在计划增加可再生能源和核能。 但是,它还打算建造大量新的燃煤电厂。 日本承诺到2030年温室气体排放量将比2013年减少26%。

Politics in Japan

日本的政治

Japan has been a significant regional power for centuries, in particular since the early 1900s. It emerged as a major economic player in the decades following the second world war. Only the US and China now have larger economies.

几个世纪以来,日本一直是重要的地区强国,特别是自20世纪初以来。它在第二次世界大战后的几十年中成为主要的经济参与者。现在只有美国和中国拥有更大的经济体。

Japan is a parliamentary democracy, but the conservative Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) has governed almost continuously since it was formed in 1955. Its current leader, Shinzō Abe, has been prime minister since 2012 and in 2016 won a snap general election. The next general election is set to take place by October 2021.

日本是一个议会民主制国家,但保守的自民党(LDP)自1955年成立以来几乎一直处于执政状态。其现任领导人安倍晋三自2012年以来一直担任总理,并在2016年赢得大选。下一次大选将于2021年10月举行。

In 1997, Japan hosted the third formal meeting of the UNFCCC (United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change) in Kyoto, its former capital. Here, it helped broker the adoption of the Kyoto Protocol, the first international treaty to reduce emissions, which took into account countries’ historical contribution to climate change and ability to implement policies. However, Japan’s own climate efforts have been criticised as inadequate.

1997年,日本在其前首都京都举办了第三次UNFCCC(联合国气候变化框架公约)正式会议。在这方面,它帮助推动了“京都议定书”的通过,这是第一个减少排放的国际条约,其中考虑了各国对气候变化的历史贡献和实施政策的能力。然而,日本自己的气候努力被批评为不足。

Plenary session in the main hall of the Kyoto International Conference Center at COP3, in 1997. Credit: UN Photo/Frank Leather.

1997年在COP3的京都国际会议中心主厅举行的全体会议。来源:联合国图片/弗兰克皮革。

After the 2011 Fukushima disaster, in which a tsunami devastated a nuclear power plant, all of Japan’s nuclear reactors were switched off. Political and public attention turned to energy saving and alternative sources of power. Japan was also recovering from the damage of the major earthquake and tsunami, which cost 16,000 lives. This led to ambitious climate policy becoming less of a focus.

Polls show 45% of Japanese people consider climate change to be a very serious problem, in the middle of the range for the world’s major economies. Concerns are highest about severe weather, over droughts, extreme heat and sea level rise.

Japan’s policies for promoting coal-fired power are leading to severe criticism internationally, according to a February 2018 report from the foreign ministry’s official advisory panel on climate change. It said:

“If Japan continues to pursue its polic[ies] incompatible with the global decarbonising efforts, Japan may be left behind, not only in [the] energy and environment sector, but also may hinder its industrial competitiveness in the global market, which now pays serious attention to carbon risks.”

Paris pledge

巴黎协定

Japan sits within the “Umbrella group” at the international climate talks overseen by the UNFCCC. It is considered to be among the most developed countries and, therefore, required to take the lead on tackling climate change. It is known as an “Annex I/II” country in UN parlance.

Japan’s GHG emissions stood at 1.2bn tonnes of CO2 equivalent (GtCO2e) in 2015, according to data compiled by the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK). Note that this includes emissions from land use, land-use change, and forestry (LULUCF).

This was equal to 2.6% of global emissions that year, slightly less than Brazil and Indonesia, but higher than Iran and Germany.

Japan’s emissions rose progressively between 2009 and 2013, as the country turned off its nuclear plants and moved to fossil fuels following the Fukushima accident. Emissions fell slightly from 2014 to 2015 and have been flat since.

Japan’s climate pledge (“nationally determined contribution”, or NDC) targets a 26% reduction in GHG emissions below 2013 levels by 2030, including LULUCF. This was submitted to the UNFCCC in the lead up to the Paris climate conference in 2015.

The pledge would reduce Japan’s emissions to around 1GtCO2e. The choice of 2013 as baseline year is unusually late, though Japan noted it means a 25% reduction on 2005 levels – a similar ambition to the now-frozen US pledge.

Japan’s NDC argues its target is consistent with long-term pathways keeping global temperatures below 2C. However, it represents only an 18% reduction on 1990 levels, well below the targets of some other developed countries. In contrast, the EU has pledged at least a 40% reduction in 1990-level emissions by 2030.

Japanese prime minister Shinzō Abe gives a speech at the UN summit on climate change in New York, in September 2014. Credit: Newscom/Alamy Stock Photo.

日本首相安倍晋三在联合国气候变化上发表演讲,纽约,2014年9月。

Climate Action Tracker (CAT) analysis rates Japan’s pledge as “highly insufficient”, meaning its promised emissions reductions are outside its “fair share” to be in line with the Paris Agreement. The pledge is not at all consistent with holding warming below 2C, let alone 1.5C, says CAT, and warming would reach 3-4C by 2100 if all government targets were akin to Japan’s.

Japan also intends to allow the use of LULUCF “credits” to meet its 2030 target, says CAT. This means improved land managements and re-vegetation would generate a credit which can be used to offset total emissions. This will effectively reduce the ambition of the target to 15% below 1990 levels, says CAT.

Meanwhile, coal plant construction plans “pose a serious risk to the government’s future mitigation efforts”, it says.

Japan’s per capita emissions stood at 10.2tCO2e in 2015. Japan’s NDC says its per capita emissions, along with progress in energy efficiency, show Japan is already “at the leading level among developed countries”. However, the UK and EU’s average per capita emissions were far lower in 2015, both at 7.7tCO2e. Japan’s NDC said it expects per capita emissions and energy efficiency to “improve” by around 20 to 40% by 2030.

It is worth noting that Japan’s population is already falling and this trend is expected to continue over the coming decades. Per capita emissions will, therefore, fall less rapidly than overall emissions reductions.

Energy policy

能源政策

Around 90% of Japan’s total GHG emissions come from energy-related activities, making these the most critical factor for its climate policy.

Energy policy in Japan lies under its Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI). This produces “basic energy plans” every three years (although the last revision was made in 2014). A revision process for the new fifth plan has been ongoing since mid-2017 and is expected to be finalised by the end of summer 2018. [Update 3/7/2018: Japan today approved its fifth basic energy plan. This left source targets unchanged from the draft plan discussed here.]

Last month, Japan released a draft version (in Japanese) of the plan. This outlined the intended mix of power sources for 2030, repeating plans first adopted in 2015.

The electricity mix should include a 20-22% share of nuclear and 22-24% share of renewables by 2030, it says. Coal should provide 26% of power and natural gas 27%. The plan also intends to reduce total electricity demand by 17% compared to a business-as-usual scenario.

Tomatō-Atsuma Power Station in Atsuma, Hokkaido, Japan. Credit: achappe/Wikimedia Commons (CC BY 2.0).

The draft plan is the first to combine the renewables and nuclear figures to make a 44% “zero-emission electricity share”. It is also the first to outline plans to make renewables “major electricity sources”, or to discuss “decarbonisation”. However, it failed to increase Japan’s renewable targets, which some had been pushing for.

The new basic energy plan is the first to include 2050 targets. It outlines multiple scenarios for 2050 based on different assumptions around renewables, fossil fuels, nuclear and hydrogen.

Nuclear

核能

Nuclear began to play a significant role in Japan’s energy mix from the mid-1970s onwards. In the decades before 2010, it produced around a quarter of the country’s electricity, as the chart below shows.

However, the 2011 Fukushima disaster drastically altered Japan’s view of nuclear energy. A tsunami caused by an earthquake off Japan’s northeast coast resulted in nuclear meltdown, with around 150,000 people evacuated due to the radiation threat. Following this, Japan quickly cut back on its use of nuclear energy and by 2013 it had shuttered all its nuclear plants. A large expansion of gas and oil provided the missing power.

In the wake of these changes, Japan announced a weakened international climate pledge in 2013. The new goal will mean a 5% rise on 1990 emissions by 2020, while the previous pledge would have reduced emissions 25% on 1990 levels. Japan is expected to overachieve its new target with current policies.

Japan’s government supports the re-commissioning of nuclear plants to help tackle energy supply strains, high energy prices and carbon emissions. The new draft 2030 energy plan describes nuclear as an “important base-load electricity source”.

Kashiwazaki-Kariwa nuclear power plant in Niigata Prefecture, shortly after the reactor’s operation was suspended for routine checkup in March 2012. Credit: Newscom/Alamy Stock Photo.

Some nuclear plants have already reopened in recent years and nuclear generation is rising. However, only seven of the country’s 42 operable plants are currently running and nuclear output remains at a fraction of its pre-2011 level. Government plans for increasing nuclear would mean both restarting nuclear plants and extending their lifetime.

Nuclear power remains contested in Japan, with a majority of people opposed to restarting reactors. Court orders and public opposition have delayed the return of nuclear plants.

Renewables

可再生能源

Japan has rapidly expanded its renewable power in recent years. Solar, wind and other non-hydro renewables produced 10% of Japan’s electricity in 2017, more than triple their production in 2012. Hydro has produced 6-8% of Japan’s electricity for decades.

By 2030, Japan expects 7% of its electricity to come from solar, 9% from hydro, 4% from biomass and 2% from wind. Together these would meet its target for 22-24% share of renewables in the power mix, up from 18% in 2017. Despite a push to set a higher 2030 renewables goal, this has reportedly been little discussed in government so far.

Since 2012, renewables have been supported by Japan’s feed-in tariff (FIT) law, which covers solar, wind, hydro, geothermal and biomass. The law obliges utilities to buy renewable electricity at a high guaranteed price, with costs paid by users.

The expansion of large-scale solar farms, in particular, has been helped by the FIT law, although this has slowed slightly in the past few years. Japan ranked fourth globally for new capacity additions in 2017, with an estimated 7 gigawatts (GW) installed, despite a slight decrease in expansion in the past few years. Japan’s solar capacity now stands at over 49GW. This is the world’s third largest, behind China and the US but ahead of Germany.

The Japanese parliament passed changes to the FIT law in 2016 to reduce its cost and better balance support between different technologies. In addition, the FIT system for large-scale solar projects was replaced with a new auction system. The first auction, held in 2017, produced significantly lower solar prices than under the FIT system. However, solar prices remain higher than in many other countries.

Photovoltaic power plant and mountain, Japan. Credit: Norikazu Satomi/Alamy Stock Photo.

Japan has relatively little wind capacity, which critics blame on a rigorous Environmental Impact Assessment procedure and difficulty in accessing the grid. Government projections only expect 1.7% of power generation to come from wind by 2030. Japan added around 0.2GW of new wind capacity in 2017, bringing its total to just over 3GW.

Geography has also been seen as a barrier to wind power development in Japan. For offshore wind, the deep waters near to its coast could limit development, although near-shore wind farms and the development of floating offshore wind technology could overcome this.

Japanese offshore wind power has “tremendous potential”, according to a 2017 report from the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA). New legislation to help promote the development of offshore wind was passed earlier this year.

Onshore wind also faces geographical constraints, including population density, fragmented electricity grids, mountainous terrain, earthquakes and typhoons. Its contribution to the renewables mix is expected to peak shortly after 2030.

Coal

煤炭

Coal power has risen in Japan since the Fukushima accident, supported in recent years by several policies to make approval of coal plants easier and cheaper. Coal accounted for 34% of Japan’s electricity production in 2017, up from 27% in 2010.

Japan has around 45 GW of operating coal plants – the sixth largest fleet in the world – according to the Global Coal Plant Tracker. It also shows Japan has 18GW of new coal-fired plants in the planning or construction phases, the biggest coal power construction plans of any developed nation.

Note, though, that only 4GW of these plants are currently under construction and some of them may not get built. Nearly a quarter of the new plants planned by the end of 2017 have been cancelled or shelved this year.

Tsuruga power plant, Japan. Credit: Joel Abroad/Flickr (CC BY-NC-SA).

In order to align with the Paris Agreement goals, Japan now needs to shift focus to how to mostly phase out all coal plants by 2030, according to scientific NGO Climate Analytics. It pointed to the UK, which is set to shut down its last coal plant by 2025, as an example of a successful coal phase-out.

Japan’s coal plants are thought to be the most efficient in the world. However, efficiency standards will not come close to bringing emissions down to what is needed under the Paris Agreement, Climate Analytics says.

Japan has not had any large-scale coal mining since it dwindled to almost nothing in 2002. It imported a record amount of coal last year, primarily from Australia. Japan’s banks are also well known for financing coal developments abroad, especially in South East Asia.

Oil and gas

石油和天然气

Japan is the world’s largest liquefied natural gas (LNG) importer and electricity accounts for the majority of gas consumption. Following the Fukushima disaster, gas-based electricity became the largest contributor to fill the gap from closed nuclear plants. It increased by around a third between 2010 and 2012, remaining at high levels ever since.

The government expects natural gas to supply 27% of the nation’s power in 2030, down from 40% today.

Japan is also the world’s third largest oil consumer and importer, behind the US and China. The use of oil to produce electricity fell over the decades up to 2010. Its use doubled in the years following Fukushima, but has since dropped to its lowest ever level, supplying 5% of electricity in 2017. The government expects it to supply 3% of power in 2030.

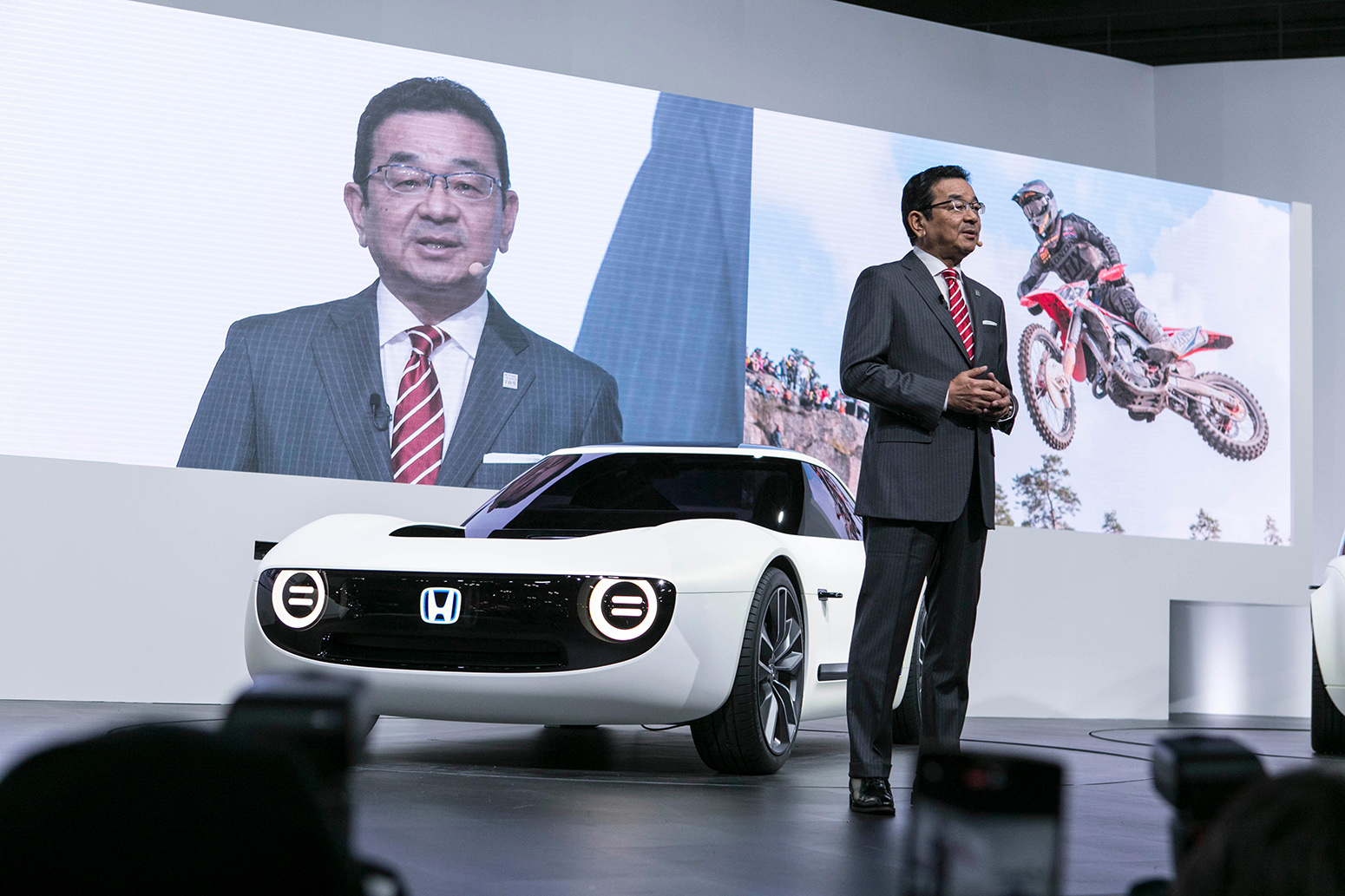

The president of Honda, Takahiro Hachigo, pictured after presenting its new concept cars at the 45th Tokyo Motor Show. Credit: Yuichiro Tashiro /Alamy Live News.

Japan’s transport and manufacturing sectors rely heavily on oil, which the government notes has highest geopolitical risk to procurement among all fossil fuels.

Japan’s government has set out a “hydrogen society” vision, which it plans to showcase at the 2020 Tokyo Olympic Games. This includes a target of putting 40,000 hydrogen-powered vehicles on the road by 2020 and doubling the number of fuelling stations to 160.

Japan has also promoted the uptake of electric and hybrid cars using subsidies and infrastructure support, and had a fleet of 150,000 in 2016. Toyota, the country’s biggest automaker, has long promoted its first hydrogen-powered car, but more recently announced plans to develop a range of electric vehicles.

Climate laws

气候变化律法

Japan’s climate policy takes place under its Act on Promotion of Global Warming Countermeasures. This was passed in 1998 and aims to reduce human-caused global warming by “formulating a plan for attaining targets”. It commits the state, local governments and companies to develop emission reduction plans.

The most recent state plan was released in May 2016. This also serves to “clarif[y] the pathway” to achieving Japan’s NDC goal. It sets out “estimated emissions” reductions in different sectors to meet the 2030 target and policies to get there.

The biggest cuts are expected to come from the commercial, residential and transport sectors. It outlines plans to improve the energy efficiency of buildings through 100% use of LED lights and installation of 5.3m fuel cells in homes by 2030. Electric or fuel cell vehicles should make up 50-70% of new sales by 2030, it says, while renewables should be expanded “to the maximum extent possible”.

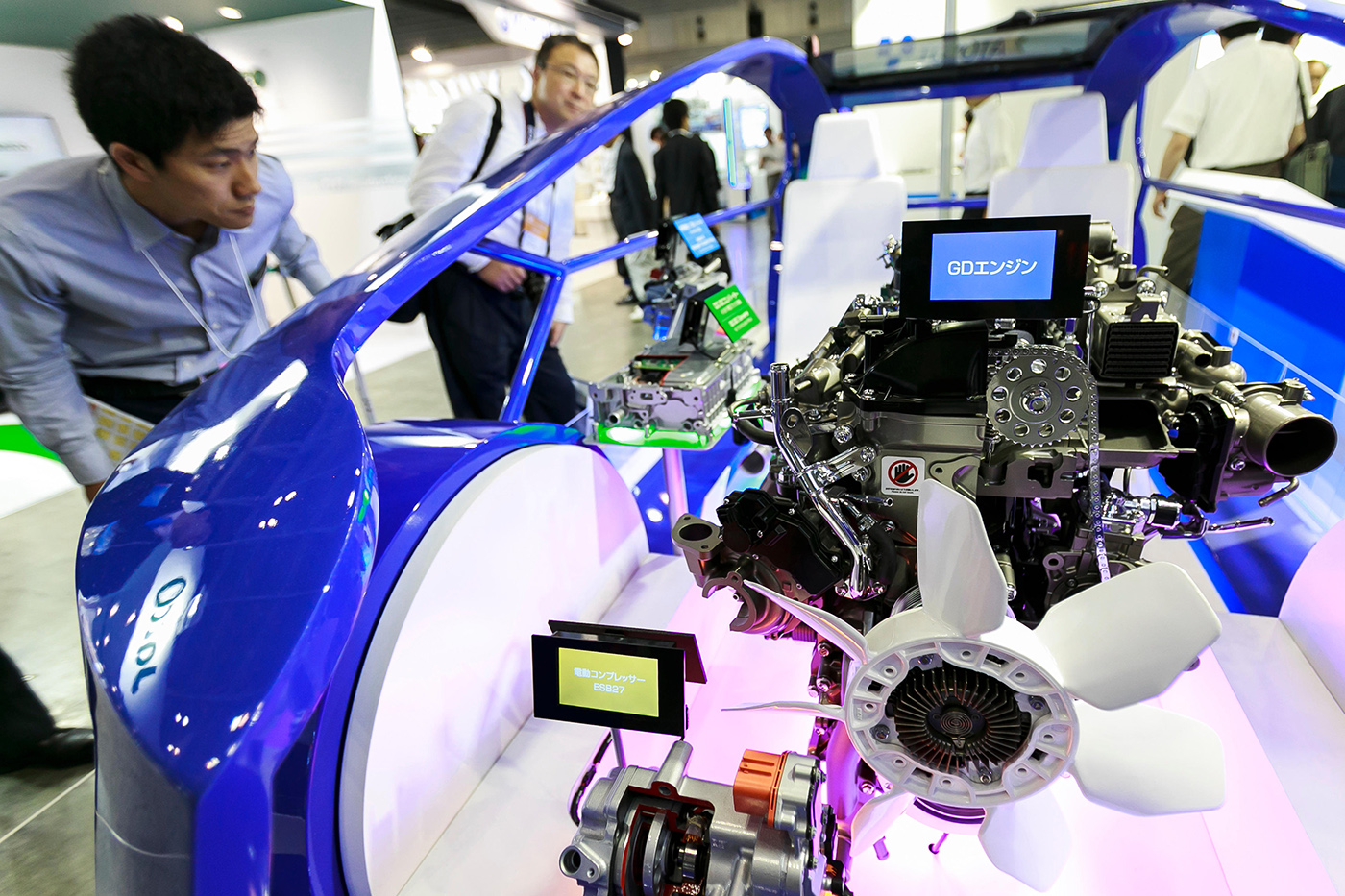

Visitors look at the hydrogen fuel cell vehicle system of the Toyota Mirai at an exposition in Yokohama, Japan, 25/05/2016. Credit: Rodrigo Reyes Marin/AFLO/Alamy Live News

The country’s law on the “rational use of energy”, enacted in 1979 due to the oil crisis, aims to promote effective use of energy, including in transport and industry. The government prides itself on its energy efficiency improvements since then and aims to improve energy consumption efficiency 35% by 2030, compared to 2012 levels.

In 2015, Japan passed regulation making energy efficiency standards for large buildings mandatory for the first time. It also aims to reduce the net energy consumption of new homes and buildings to zero by 2030.

Japan has a long-term goal to reduce its greenhouse gases by 80%, though it gives no baseline year for this. The goal was set back in 2012 and re-stated in the 2016 climate plan.

It is now developing a long-term emissions strategy up to 2050, due to be submitted to the UNFCCC by 2020. Japan is expected to finalise it before hosting the G20 summit in May 2019.

CAT has expressed concern over Japan’s long-term strategy. It says that two government ministries – the Ministry of the Environment (MOEJ) and METI – have published separate reports on the strategy with “fundamentally different directions”. It says:

“The MOEJ focuses on how to achieve the 80% by 2050 reduction target domestically, and emphasises a need for the early introduction of a fully-fledged carbon pricing scheme.

In complete contrast, the METI emphasises the difficulty of achieving the 80% reduction domestically and focuses instead on Japan’s international contribution to global emissions reductions. The METI report is also critical about any introduction of a full-fledged, nationwide carbon pricing in the near-term.”

Japan’s environment ministry is currently working on a carbon pricing proposal, although opposition remains in parts of the government. Last year, Japan’s environment minister called carbon pricing “the most efficient tool” to help achieve the 2050 target.

In 2012, Japan implemented a carbon tax on oil, gas and coal imports, with revenues going towards measures to curb CO2 emissions. The price of this remains very low at under $3 per tonne CO2e.

Impacts and adaptation

影响与适应

Japan is vulnerable to several impacts of climate change, including sea level rise, coastal erosion, more intense typhoons and summer droughts.

Some research has shown the effects of climate change already being felt in Japan. One 2013 paper found several ecological changes occurring due to climate change, including delays in the first springtime appearance of some insects.

Meanwhile, the Japan Metrological Agency says long-term temperature rises due to global warming may have contributed to this year’s early blooming of cherry trees. The culturally significant trees have been flowering a day earlier every decade since 1953, the agency says.

In March 2015, Japan’s Central Environment Council released a 108-page impact assessment of the current and possible future impacts of climate change across seven sectors, from agriculture to human health.

Cherry Blossom in Gyoen National Garden, Shinjuku, Tokyo, Japan. Credit: Oleksiy Maksymenko Photography/Alamy Stock Photo.

The report noted, for example, a projected decline in the quality of rice due to rising temperatures. It also said Japan’s current vulnerability to floods means more severe rainfall conditions due to climate change could have “considerably high” impacts.

The government followed up this impact assessment in November 2015 with its 107-page National Adaptation Plan. This outlined how climate adaptation in the seven sectors should be “mainstream[ed]” into government policy. The next plan is due in or before 2020.

In February 2018, Japan’s cabinet approved a bill to address the damage from already locked-in effects of climate change. The bill commits the environment ministry to assessing climate change impacts every five years and municipalities to developing adaptation plans. The bill is expected to be enacted by Japan’s two parliamentary chambers this summer.

Japan is obliged to provide climate finance to other countries, due to its Annex II status at the UNFCCC. It is the third biggest donor to multilateral climate funds after the US and UK, Carbon Brief analysis showed last year.

Most significantly, it has pledged $1.5bn to the Green Climate Fund (GCF), established to leverage climate finance towards the $100bn per year promised by developed countries by 2020.

This means Japan is now, in effect, the GCF’s largest donor. The US, which had pledged $3bn to the fund, has said it now plans not to follow through on $2bn of this.