作者:Eric Roston@erostonMore stories

by Eric Roston

日期:2018.05.18

链接原文:https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-05-18/carbon-capture-the-vacuum-cleaner-the-climate-needs-quicktake

In the North Sea, removing the gas, storing

the carbon.

Photographer: Heidi Wideroe

We humans are all too good at putting

carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. Can we come up with a way to vacuum it out?

Scientists, engineers and governments are focusing on technologies that capture

carbon to buy time as the global economy tries to kick the fossil-fuel habit.

But as predictions of the climate’s trajectory grow more dire, the most

authoritative studies are concluding that large-scale carbon removal -- enough

to massively reduce absolute carbon levels, not just lower the rate of increase

-- is humanity’s best hope of avoiding calamity. Current technology is a long

way from being able to help.

1. Couldn’t we just plant a gazillion trees?

Don’t laugh. Trees are the original carbon

scrubbers. A group of scientists wrote that including "natural climate

solutions” -- mainly reforestation, or planting trees -- among other measures

could produce 37 percent of the cuts needed by 2030 to put the world on track

to meet the goal of the 2015 international Paris agreements, which is to limit

warming to 2.0 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) above mid-19th century

levels. One catch: That much tree-planting might require high-quality land

three times the size of India.

2. How much carbon needs to be taken from the environment?

We’ve already put 45 percent more carbon

dioxide into the air than there was before industrialization. Every day,

another 100 million metric tons of it goes up. Reducing those emissions to zero

-- if that can even be done -- would not be enough to meet the 1.5 degree goal.

(We’re up about 1 degree Celsius already.) By one estimate, between now and

2100, we’d need to remove more than 800 gigatons of CO2, the equivalent of 20

years of emissions at current rates.

3. What does carbon removal mean?

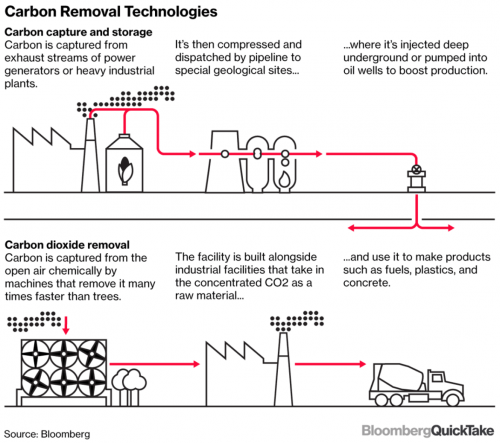

It comes in two main flavors: carbon

capture and storage (CCS), and carbon dioxide removal

(CDR). Capture-and-storage has gotten most of the attention so far, largely

because it’s been promoted by the coal industry as the thing that will solve

its emissions problems. It means collecting CO2 as it’s being emitted by

fossil-fuel generators or industrial facilities, then sending it for use

elsewhere or for storage deep underground. When you hear of "clean coal,” it’s

usually a reference to CCS.

4. How well do CCS projects work?

They work, but mostly haven’t moved past

the testing stage. There are

more than 20 CCS projects around the world, and dozens more smaller-scale

efforts. The field’s biggest black eye is a gas-and-coal

plant in Mississippi equipped for carbon capture that came in more

than three times over its original $2.4 billion budget and is no longer

capturing carbon. In a recent report, Royal Dutch Shell suggests that we’d need

10,000 large-scale CCS facilities by 2070 to meet the 2-degree goal.

5. Can CCS save the coal industry?

Probably not, even with tax credits for

sequestering CO2 that were expanded in February. Natural gas is so cheap that

coal has a hard time competing, even without the (significant) added costs of

installing CCS. The biggest beneficiary has been the oil industry, which has

claimed more than $1 billion in credits by buying concentrated CO2 and injecting

it into aging oil fields, where the gas helps declining wells produce more.

6. Then what’s the prospect for CDR?

CDR pulls carbon dioxide out of the ambient

air, which is even more difficult than capturing it when concentrated in an

exhaust flue. Still, research labs and startups are developing competing

methods for so-called reversible reactions, in which CO2 is dissolved in

chemicals and then released. Zurich-based Climeworks AG, for

instance, builds large banks of filters that suck in air, combine the CO2 with

chemicals called amines, and release the clean air out the other side. The CO2

is collected and concentrated for industrial use, such as making plastic or

concrete. Global Thermostat LLC, in New York, also

uses nitrogen-based chemicals to collect and concentrate CO2, while Carbon Engineering Ltd. of British

Columbia captures it in calcium carbonate before separating it out again.

7. How effective is CDR?

It’s mostly still in the demonstration

phase. The first commercial Climeworks plant can take 900 tons of CO2 out of

the air every year. But more than 400,000 such plants would be needed to cancel

out 1 percent of current emissions. That’s the kind of figure that has

scientists hoping for some other kind of radical breakthrough.

8. Are there other approaches?

Yes. One is a variation of CCS called

bio-energy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS). First, plants are

grown that absorb CO2. Then that biomass is burned to generate power. Those

emissions are captured and buried, making for a carbon-negative power system.

Here again, the amount of land that would be needed to grow enough biomass is

many times the size of India. One trait BECCS shares with reforestation, CCS

and CDR -- they’d all seem more feasible if the widespread adoption of carbon

taxes tilted economic incentives away from activities that produce greenhouse

gases and toward those that suck them up.

The Reference Shelf

l An International Energy Agency report: 20 Years of Carbon

Capture and Storage.

l The Center for Carbon Removal’s overview of approaches to carbon capture.

l The National Energy Technology Laboratory’s portal for carbon capture.

l Carbon Brief’s 2016 series on "negative

emissions."

l The European Academies Science Advisory Council’s report on "negative

emissions" and the Paris Agreement.

l The $20 million carbon XPRIZE has companies competing

to turn captured-carbon into products.

l A visit

to the Mississippi carbon capture coal power plant that became a symbol of the

technology’s shortcomings.